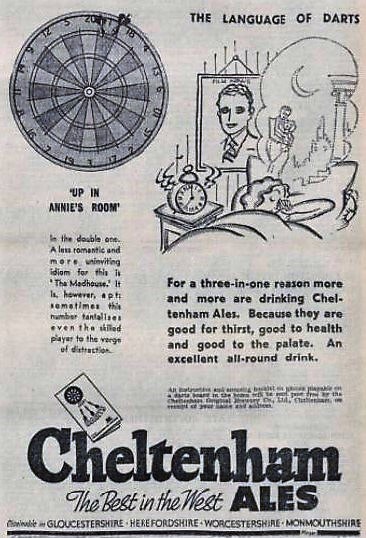

‘UP IN ANNIE’S ROOM’

advertisement for Cheltenham Ales – Gloucestershire Echo – 1st April 1937

In Dictionary of English Phrases (Penguin Books – 2006), Robert Allen writes that the informal phrase up in Annie’s room is used in answer to an enquiry about a person’s whereabouts, either because the speaker doesn’t know or because they are unwilling to say.

According to him, the phrase dates from forces’ slang in the First World War. And it is true that, in the form in Annie’s room, it is first recorded in several glossaries of soldiers’ slang published in the years following World War One; for instance, the following definitions are from Digger Dialects: A Collection of Slang Phrases used by the Australian Soldiers on Active Service (Melbourne and Sydney, 1919), by Walter Hubert Downing:

“In Annie’s room”—an answer to questions as to the whereabouts of someone who cannot be found. (See “Hung on the wire”).

[…]

Hung-on the wire—Absent; missing.

Likewise, in Soldier and Sailor Words and Phrases (London, 1925), Edward Fraser and John Gibbons wrote:

Annie’s room, in: An expression by way of jesting answer to an enquiry for someone who cannot be found, e.g., “Where is Private Smith?” “In Annie’s room” (see Barbed wire).

[…]

Barbed wire, on the: Primarily meaning killed. Also used familiarly of any absent man; e.g., “Where is Robinson?” “Hanging on the barbed wire.” Every attack, of course, left a number of men killed in getting through the enemy’s wire entanglements and literally hanging there.

However, it is important to stress that there seems to exist no authentic quotation dating from World War One that supports this origin. The only occurrence of Annie’s room from that period that I have found has a different meaning; it is from the Gloucester Journal (Gloucester, Gloucestershire) of Saturday 25th March 1916, in the review of “the descriptive sketch of a day at the front […] presented by wounded soldiers from Hillfield V.A. Hospital” performed at the Gloucester Hippodrome on 23rd:

The sketch was set in appropriate scenery, notices indicating that the spot was “Hell’s Corner, Plug Street,” that out over the parapet was “Berlin,” and in the rear “Blighty,” the name (corruption of an Indian word) given by our Tommies to home. The dug-outs were named “Fortunes of War,” Bon Marché,” “Annie’s Room,” etc.

The earliest two uses of the phrase that I have found date from May 1931 and both refer to the same story; the first occurrence is from The Worthing Herald (Worthing, Sussex) of Saturday 2nd May:

“In Annie’s Room!”

“Up in Annie’s room!” shouted Frederick Smith, of Cortis-avenue, Worthing, when a police-constable hailed him and told him he was riding his bicycle without a front light. Later the officer saw him in a shop. The defendant was fined 5s.

The second instance is clearer; it is from the Littlehampton Gazette (Littlehampton, Sussex) of Friday 8th May:

“Up in Annie’s Room.”

A FLIPPANT ANSWER—AND FIVE SHILLINGS.“Where’s your light? asked Police-constable Pennicott, as Frederick Smith, 44, Cortis-avenue, Worthing, rode past him at Broadwater on the night of April 21st.

“Up in Annie’s room!” retorted Smith, and rode on.

Failing to see the joke—if there was one—the police officer gave chase, and when Smith came out of a fish-and-chips shop he taxed him with riding without a light. Smith said he had walked; the police constable was confident he had ridden, and the result was that Smith was summoned before the Magistrates on Wednesday, and fined 5s.

The choice of Annie is unexplained; it was probably just a random use of a common enough name in the sense of any woman.

It is said that the phrase was later extended to behind the clock and to behind the wallpaper—but, in this case too, no authentic instance seems to have been recorded.

In dart-players’ slang, up in Annie’s room has been in use since 1937—whether it was borrowed from the answer to an enquiry about a person’s whereabouts or coined independently is not known. The earliest instance that I have found is from an advertisement for Cheltenham Ales, published in the Gloucestershire Echo (Gloucester, Gloucestershire) of Thursday 1st April 1937; Cheltenham Original Brewery Co. was to send post free, on receipt of the reader’s name and address, “an instructive and amusing booklet on games playable on a darts board in the home”:

‘UP IN ANNIE’S ROOM’

In the double one. A less romantic and more uninviting idiom for this is “The Madhouse.” It is, however, apt; sometimes this number tantalises even the skilled player to the verge of distraction.

The dart-players’ phrase was defined in The Lingo of Darts, published in the Boston Guardian (Boston, Lincolnshire) of Wednesday 20th December 1939:

Few games are so rich in quaint idioms as darts. Many survive from the days when “puff darts” was a popular game in most inns. This was played with a long brass tube through which was propelled by the player’s breath a small, light-feathered dart.

“Kelly’s eye” and “Clickety-click” represent the same numbers, 1 and 66 respectively, as they do in the familiar game of “Housey-housey,” as “Connaught Rangers” stands for 88. But what of “Bag o’ nuts” and “Bull calf”? The former stands for 45 and the latter for 33, though just why I don’t know. “In the madhouse” expresses a double-one, and “In the wilderness” means that the player needs 99 for game—99 being the dart player’s unlucky number.

“Up in Annie’s Room”

Failure to score is denoted by “Oxo” and a score of 100 is a “Ton.” Three darts in one section is known as “Three in a bed” and a bull’s eye as “Pug.” To score 42 is to secure “The Weaver’s Donkey,” while the number 26 is “Bed and breakfast,” an idiom probably arising from the figures representing the charge for such accommodation at many inns. “Up in Annie’s room” or “Up in the Attic” refers to the space at the top of the board where scores are doubled.

“Dry wipe” means that two of three legs have been won straight out, and “Leg and leg” that each side has won a leg. The area on the left of the board, where the numbers are of high average, is known as “The married men’s side” and the cry of “Blacking back!” warns the thrower that his foot is over the line.

The meaning of Annie’s room is unclear in the following passage from Mr. Manchester Says That Those Old Cornish Saints Were Fierce Fellows (apparently the diary of a Mancunian visiting Cornwall), published in the Manchester Evening News (Manchester, Lancashire) on Wednesday 12th April 1939:

Favourite game at “The Rising Sun” is shove-halfpenny. Untutored Northerners come here to learn the mysteries of “Annie’s Room” from the coastguard, the postman, and the skipper of the three-times-daily St. Gerrans.

I have my third lesson to-night; hope to get my revenge…

The phrase used as an answer to an enquiry about a person who cannot be found has sometimes been conflated with the dart-throwers’ expression, as in this anecdote about the Women’s Auxiliary Territorial Service related in The Daily Mirror (London) on Thursday 11th January 1940:

The Girls in Uniform are “showing a leg” half-an-hour earlier these cold, raw mornings.

They tumble out of bed, throw on their tunics and skirts, rush through breakfast, and then get down to half-an-hour’s serious work—darning, sewing, knitting.

Why so early?

Because they spent their off-duty hours the night before playing darts.

In one W.A.T.S. depot, they’re still laughing over a little episode.

The stern-faced commandant walked into the mess.

A group of girls clustered round the dartboard in a corner.

In Annie’s Room

“Where’s Sergeant Blank?” she demanded.

“Up in Annie’s room!” came the reply.

Which wasn’t insubordination, but merely darts dialect inferring that sought-after sergeant was struggling to get a double one.