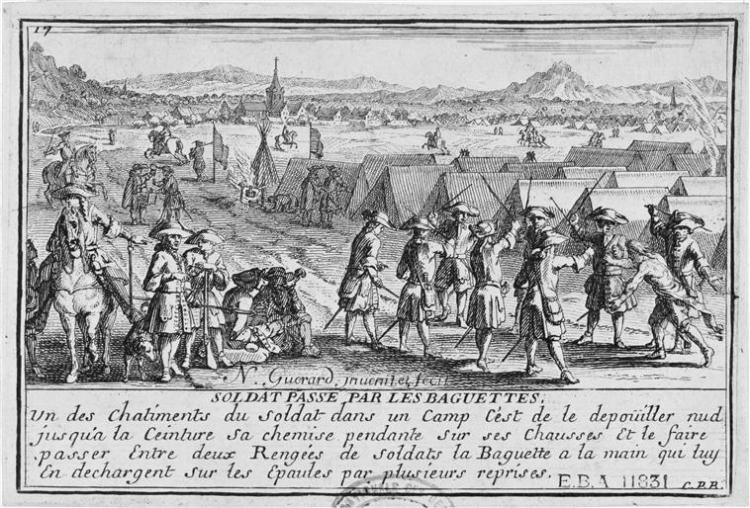

SOLDAT PASSE PAR LES BAGUETTES.

Un des chatiments du soldat dans un camp c’est de le depouiller nud jusqu’a la ceinture sa chemise pendante sur ses chausses et le faire passer entre deux Rengées de soldats la Baguette a la main qui luy en dechargent sur les epaules par plusieurs reprises.

translation:

SOLDIER MADE TO PASS THROUGH THE STICKS.

One of the soldier’s punishments in a camp is to strip him naked to the waist, his shirt hanging onto his breeches, and make him pass between two rows of soldiers, who, with the stick in their hand, hit him several times on the shoulders.

from L’art militaire ou Les Exercices de Mars, livre à dessiner

(Nicolas Guérard, Paris, circa 1695)

image: Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais / Musée de l’Armée, Paris

The phrase to run the gauntlet means to go through an intimidating or dangerous crowd or experience in order to reach a goal.

The English noun gauntlet in the current sense of a heavy glove with a long cuff is from French gantelet, diminutive of gant, meaning glove.

But in the phrase, gauntlet, attested in 1676, is an alteration by association with gauntlet, glove, of the obsolete noun gantlope, first recorded in 1646, from Swedish gatlopp, literally, a lane run, composed of gata, a lane, and lopp, a run.

(The Swedish noun gata is related to English gate in the sense of a way, a street, as in street-names of northern and midland towns such as Gallowgate and Kirkgate. The word lopp is related to leap.)

The phrase to run the gantlope, later the gauntlet, originally designated a military, also occasionally naval, punishment in which a culprit was stripped to the waist and made to run between two rows of men who aimed blows at him with sticks, or knotted ropes in the Navy (cf. also cat o’-nine-tails). In Glossographia: or A Dictionary, Interpreting all such Hard Words, Whether Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, Teutonick, Belgick or Saxon, as are now used in our refined English Tongue (1656), the English antiquary and lexicographer Thomas Blount (1618-79) thus defined the word gantlope―he misidentified the origin of the element gant:

Gantlope (Ghent Lope), a punishment of Souldiers, first invented at Ghent, or Gant in Flanders, and therefore so called. Lope in Dutch signifies running; for the Offendor is to run through the whole Regiment with his upper part naked, and every fellow-Souldier to have a whip at him, &c.

The Swedish word probably became known in England through the Thirty Years’ War, a European war of 1618-48 which broke out between the Catholic Holy Roman emperor and some of his German Protestant states and developed into a struggle for continental hegemony, with France, Sweden, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire as the major protagonists. It was ended by the Treaty of Westphalia.

One of the earliest figurative uses of the phrase is from The church-history of Britain from the birth of Jesus Christ until the year M.DC.XLVIII (London, 1655), by the Church of England clergyman Thomas Fuller (1607/8-1661):

This Petition ran the Gantlop throughout all the Prelaticall party, every one giving it a lash, some with their Pens, moe [sic] with their Tongues.

The French equivalents of to run the gauntlet were:

– military punishment: passer par les baguettes, to pass through the sticks; (faire) passer un soldat par les baguettes, to make a soldier pass through the sticks;

– naval punishment: courir la bouline, to run the bowline (bouline is from the English word now spelt bowline; both denote a rope).

The French writer, playwright and poet Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet – 1694-1778) evoked the military punishment in Candide, ou l’Optimisme (1759):

original edition:

On lui demanda juridiquement ce qu’il aimait le mieux, d’être fustigé trente-six fois par tout le Régiment, ou de recevoir à la fois douze bales de plomb dans la cervelle ; il eut beau dire que les volontés sont libres, & qu’il ne voulait ni l’un, ni l’autre, il fallut faire un choix ; il se détermina en vertu du don de Dieu, qu’on nomme liberté, à passer trente-six fois par les baguettes ; il essuïa deux promenades. Le Régiment était composé de deux mille hommes ; cela lui composa quatre mille coups de baguettes, qui, depuis la nuque du cou jusqu’au cû lui découvrirent les muscles & les nerfs. Comme on allait proceder à la troisiéme course, Candide n’en pouvant plus demanda en grace qu’on voulût bien avoir la bonté de lui casser la tête.

translation (from Candid: or, The Optimist – London, 1762):

He was asked which he liked best, either to run the gauntlet six and thirty times through the whole regiment, or to have his brains blown out with a dozen of musket balls. In vain did he remonstrate with them that the human will is free, and that he chose neither; they obliged him to make a choice, and he determined, in virtue of that divine gift called free-will, to run the gauntlet six and thirty times. He had gone through his discipline twice, and the regiment being composed of 2000 men, they composed for him exactly 4000 strokes, which laid bare all his muscles and nerves from the nape of his neck to his rump. As they were preparing to make him set out the third time, our young hero unable to support it any longer, begged as a favour they would be so obliging as to shoot him through the head.