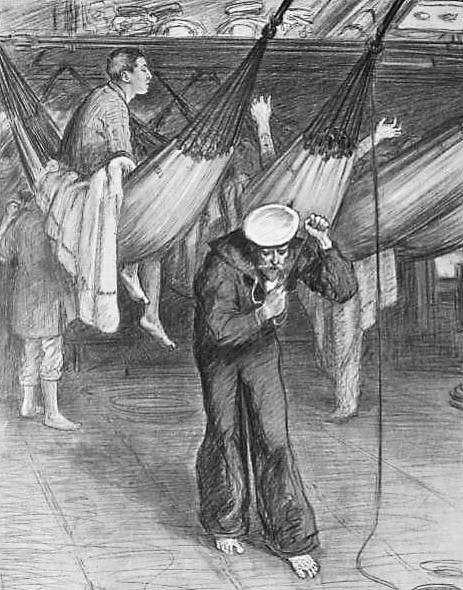

HOW A SAILOR BEGINS HIS DAY’S WORK

A Scene on board H.M.S. “Trafalgar.”The boatswain blows his whistle at 5 o’clock in the morning and cries, “All hands.” Diving in and out beneath the hammocks he goes with bent head calling the same old cry of Nelson’s day: “Rise and shine. Show a leg—show a leg—not a purser’s stocking. Rise and shine—rise and shine—show a leg.”

from The Sphere (London) – 3rd August 1901

Of naval origin, the phrase show a leg means get out of bed. On board ships, it took the additional meaning report immediately for a given task.

It is first recorded, with the form shew, in Travels of four years and a half in the United States of America; During 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801, and 1802 (London, 1803), by the British author John Davies (1774-1854):

– Mr. Adams. Call the watch.

– Cunningham.—(striking the deck with a hand-spike) Starboard-watch ahoy! Heave out there! Heave out! Shew a leg there! Shew a leg! Must I send a hauling-line down for you starbaulins¹? Hoa! the watch ahoy! I am getting my knife ready to saw your bed-posts.

(¹ the starbolins: the men of the starboard watch; the port watch and the starboard watch are the two watches into which the officers and crew of a vessel are divided.)

Another early use of the expression, this time with the form show, is from Ships of War (London, 1824), by the British missionary to seafarers George Charles Smith (1782-1863):

The boatswain’s mate ran along the deck under the hammocks calling out, “Turn out there, turn out there, every man jack of you. Show a leg there, show a leg there. Come, skulkers, tumble up.”

In the same book, Smith explained the origin of show a leg:

This is a mode of expression in the navy by the boatswain when he is calling the crew up from their hammocks; that by showing a leg they may convince him they are not asleep, and are ready to jump out quickly. It becomes at last the cry of all on board when they want a man to be expert.

In An Old Sailor’s Yarns (New York, 1835), the American author Nathaniel Ames (1805-35) gave the following explanation:

“All the starboard watch, ahoy! Rouse out there, starbowlines―show a leg or an arm!”

This last phrase designates the manner in which “turning out” of a hammock is accomplished, which hammock, a person unacquainted with such kind of sleeping accommodations, would never dream contained a live man, until one or the other of the aforementioned limbs was protruded.

In The Sailor’s Word-Book (London, 1867), the British naval officers William Henry Smyth (1788-1865) and Edward Belcher (1799-1877) explained:

Show a leg! An exclamation from the boatswain’s mate, or master-at-arms, for people to show that they are awake on being called. Often “Show a leg, and turn out.”

Finally, the following is from Sailors’ Language: A Collection of Sea-terms and their Definitions (London, 1883), by the English author William Clark Russell (1844-1911):

Show a leg!―“Show a leg, there!” means, “Show yourself” on the order being given to turn out.

According to the available written instances of the phrase, it was about fifty years after its first attestation that it began to be used extended to a purser’s stocking preceded by a connecting word:

– In Kathay: A Cruise in the China Seas (New York, 1852), by the American author W. Hastings Macauley:

“Got to see the hammocks up! six bells², come turn out,” “rouse and bitt³,” “show a leg in a purser’s stocking.”

(² On board ships, time was measured according to the number of bells and the watch. Time was announced every half-hour by a number of strokes on the ship’s bell: one bell was half an hour, two bells an hour, etc., and finally eight bells was four hours – the end of the watch.)

(³ rouse and bitt: wake up and get out of bed promptly – to bitt: to coil or fasten (a cable) upon the bitts)

– In Man-of-War Life: A Boy’s Experience in the United States Navy (Cincinnati, 1856), by the American writer Charles Nordhoff (1830-1901):

“Rouse and bit,” “show a leg―or a purser’s stocking.”

– In A Sailor’s Log-Book from Portsmouth to the Peiho (London, 1862), written by an English seaman, and edited by Walter White:

“Rouse out, here! rouse out! Show a leg and a purser’s stocking! Rouse and bit: lash away! lash away!”

In A Dictionary of Sea Terms (London, 1898), A. Ansted gave the following definition:

Purser’s stocking.—A “slop” article, and therefore capable of fitting any man, or, at least, of stretching itself to any man’s fit.

The plural noun slops designated the ready-made clothing, and other furnishings, supplied to seamen from the ship’s stores.

In the above-mentioned wordbook, Smyth and Belcher detailed the purser’s duties:

Purser. An officer appointed by the lords of the admiralty to take charge of the provisions and slops of a ship of war, and to see that they were carefully distributed to the officers and crew, according to the printed naval instruction. He had very little to do with money matters beyond paying for short allowance. He was allowed one-eighth for waste on all provisions embarked, and additional on all provisions saved; for which he paid the crew. The designation is now discarded for that of pay-master.

FOLK ETYMOLOGY

Various ‘etymologists’, who create a semblance of truth by copying from each other, explain the phrase show a leg on the following erroneous pattern, which they embellish with diverse details:

Sailors were often refused shore leave whilst a ship was in port for fear that they might desert, particularly as many of them would have been pressed against their will into service. To compensate, civilian women were allowed to live on board for the duration of the ship’s stay. In the mornings, the boatswain called the hands with a shout of ‘show a leg’. If a woman’s leg appeared – says this ludicrous explanation – she was to stay in the hammock or in the bunk until the men had left.

Those who propagate this theory argue that it is supported by the fact that the phrase was also show a leg or a purser’s stocking: they shamelessly claim that when the boatswain saw a stockinged leg sticking out from the hammock or from the bunk, he knew it belonged to a woman, and she was allowed to stay.

This explanation makes no sense. In the first place, why would these women be wearing purser’s stockings? More importantly, women are absent from all the contexts in which appear the early instances of show a leg, whether or not extended to a purser’s stocking preceded by a connecting word; the order was given to the sailors alone. The following passage from A Sailor’s Fate, by ‘Nauticus’, published in The Daily Freeman (Kingston, New York) of 18th February 1874, clearly shows the meaning of the extended form of the phrase:

“Come, rouse out there below and show a leg with a purser’s stocking on it!”